LHC data are exotic, they are complicated and they are big. At peak performance, about one billion proton collisions take place every second inside the CMS detector at the LHC. CMS has collected around 64 petabytes (or over 64,000 terabytes) of analysable data from these collisions so far. Along with the many published papers, these data constitute the scientific legacy of the CMS Collaboration, and preserving the data for future generations is of paramount importance. “We want to be able to re-analyse our data, even decades from now,” says Kati Lassila-Perini, head of the CMS Data Preservation and Open Access project at the Helsinki Institute of Physics. “We must make sure that we preserve not only the data but also the information on how to use them. To achieve this, we intend to make available through open access our data that are no longer under active analysis. This helps record the basic ingredients needed to guarantee that these data remain usable even when we are no longer working on them.” CMS is now taking its first steps in making up to half of its data accessible to the public, in accordance with its policy for data preservation, re-use and open access. The first release will be made available in the second half of 2014, and will comprise of a portion of the data collected in 2010. Although in principle providing open scientific data will allow potentially anyone to sift through them and perform analyses of their own, in practice doing so is very difficult: it takes CMS scientists working in groups and relying upon each others' expertise many months or even years to perform a single analysis that must then be scrutinised by the whole collaboration before a scientific paper can be published. A first-time analysis typically takes about a year from start of preparation to publication, not taking into account the six months it takes newcomers to learn the analysis software. CMS therefore decided to study a concrete use-case for its open data by launching a pilot project aimed at education. This project, partially funded by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, will share CMS data with Finnish high schools and integrate them into their physics curriculum. These data will be part of a general platform for open data provided by Finland’s IT Center for Science (the CSC). [UPDATE (November 2014): After the initial pilot planning with the CSC, the full development of the platform was done at CERN, with the support of the IT and Library services.] CMS data are classified into four levels in increasing order of complexity of information. Level 1 encompasses any data included in CMS publications. In keeping with CERN’s commitment to open access publishing, all the data contained in these documents and any additional numerical data provided by CMS are open by definition. Level 2 data are small samples that are carefully selected for education programmes. They are limited in scope: while students get a feel for how physics analyses work, they cannot do any in-depth studies. Level 3 is made of data that CMS scientists use for their analyses. They include meaningful representations of the data along with simulations, documentation needed to understand the data and software tools for analysis. CMS is making these analysable Level-3 data available publicly, in a first for high-energy physics. Level 4 consists of the so-called “raw” data –– all the original collision data without any physics objects such as electrons and particle jets being identified. CMS will not make these public.

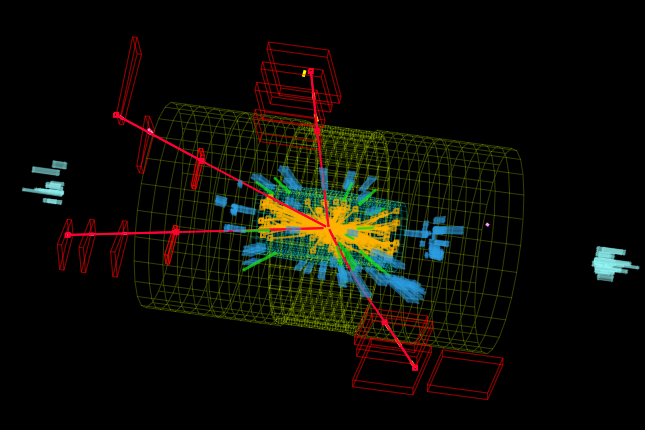

Example of public CMS Level-2 data being used in an online event display. Image: Achintya Rao / Tom McCauley

One aim of the pilot project is to enable people outside CMS to build educational tools on top of CMS data that will let high-school students to do some simple but real particle-physics analysis, a bit like CMS scientists. “We want to create a chain where the CSC as an external institute can read our data with simplified analysis tools and convert them into a format adapted for high-school-level applications,” explains Lassila-Perini. Such a chain is crucial for making the CMS data accessible to wider audiences. Within the collaboration, you need a lot of resources to perform analyses, including lots of digital storage and distributed computing facilities. “If someone wants to download and play with our data,” cautions Lassila-Perini, “you can’t tell them to first download the CMS virtual-machine running environment, ensure that it is working and so on. That’s where we need data centres like the CSC to act as intermediate providers for applications that mimic our research environment on a small scale.” Finland is an ideal case to pilot a programme that formally introduces particle physics into school curricula. 75% of Finnish high schools have classes that have visited CERN as part of their courses, and thanks to CERN's teacher programmes many of their teachers are familiar with the basics of particle physics. An ongoing survey of the teachers will help understand their perspectives on teaching data analysis in their classrooms and take on board ideas for potential applications. Lassila-Perini has big dreams. “Imagine a central repository of particle-physics data to which schools can sign in and retrieve data,” she says. “They collaborate with other high schools, develop code together and perform analyses, much like how we work. It is important to teach not just the science but also how science works: particle physics research isn’t done in isolation but by people contributing to a common goal.”

High-school students analysing CMS data. Image: Marzena Lapka

Ongoing success stories with open CMS data set the stage for the pilot project. For example, the CMS Physics Masterclasses exercise, developed by QuarkNet and conducted under the aegis of the International Particle Physics Outreach Group, as well as projects such as the I2U2 e-Labs introduce particle physics to thousands of high-school students around the world each year by teaching them to perform very simple analyses with Level-2 CMS data. A second project with more academic goals is being undertaken by CMS members at RWTH Aachen University in Germany where third-year undergraduate physics students analyse Level-2 CMS data using web-based tools, as part of courses on particle and astroparticle physics. Among other things, they learn how to calculate the masses of particles produced at the LHC.

The VISPA analysis environment developed at RWTH Aachen for analysing public CMS data. Image: Robert Fischer

An independent use-case for public CMS data comes from the field of statistics. A group of statisticians from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) have found the Level-2 data sample to be a perfect testing ground for different statistical models. This excites Lassila-Perini. “When you provide data this way, you are not defining the end users –– open data are open data!” she exclaims. There is no doubt that other fields of science will also benefit from the release of particle-physics data by CMS. The success of the pilot project will guide future open data policies, and CMS is well placed to lead the field.

- Log in to post comments